Dr. Sami Koskinen, VTT

A conventional car knows very little about road weather. It might notice that the front camera is blocked and switch off the lane-keeping assist. Or it discovers only under braking how little friction there actually is between tyres and road, and then starts searching for an appropriate braking style.

For an automated vehicle, this kind of reaction is not enough. It should be able to assess the situation much more precisely:

- do I reliably see 15 or 50 metres ahead,

- do I see far enough to the side at an intersection,

- and is it safe to overtake, or even keep my current speed?

Within the Cynergy4MIE project, VTT’s role in Supply Chain 1 is to focus on automated driving and perception in winter conditions. In Demo 1.1, we concentrate on turning bad weather into a measurable quantity: visibility, expressed in metres, in different directions.

Safety margins are more than just maths

In our previous work, we have approached automation safety through very concrete questions: how quickly the automation can react, and what level of deceleration is still considered “reasonable” – both for passenger comfort and for cargo.

At the same time, we have to ask what is an appropriate gap in the traffic flow, from a liability perspective, for a self-driving vehicle to merge into. For example, other drivers are typically assumed to react within two seconds at the latest in order not to be considered negligent – and to apply at least some braking, regardless of what the automated vehicle does.

The outcome of these calculations and interpretations is always some kind of safety margin:

- how large a gap must be kept to the vehicle in front,

- how much free space must be visible at an intersection,

- how the sudden movement of a pedestrian or cyclist is taken into account.

The strength – and challenge – of automation is that these choices can be made very consciously. We can design the system to drive “like a human”, with relatively small gaps and similar risks as everyone else, or avoid risks with an intentionally conservative strategy where every pedestrian is treated as an unpredictable child.

Where we finally draw the line is a value judgment, not just an engineering decision.

There are also countries and environments where traffic is so dense that safety margins guaranteeing “absolute safety” simply do not fit – traffic becomes more like continuous cooperation.

Snowfall, blind spots and visibility in metres

In early 2025 we collected a large amount of data in Lapland with our Heluna automated vehicle (Figure 1). Heluna is equipped with a front-facing gated camera, standard camera, a 4D radar and two lidars, along with inertial sensors.

Figure 1. VTT’s Heluna automated vehicle

During the measurement campaign we saw how snowfall and rain can reduce the practical range of sensors to just a few tens of metres, even if the data sheets promise up to 200 metres. A dense and reliable point cloud often ends at around 50 metres – beyond that, the information becomes sparse and estimates require data fusion from different sensors.

At the same time, the vehicle must still be able to handle rare but realistic situations, such as:

- a pedestrian suddenly running out from behind a parked van or a snowbank,

- an intersection where a high snowbank blocks the view to the side almost completely.

A human driver often slows down based on intuition: “I can’t really see to the left, so I’ll drive more slowly.” A self-driving vehicle needs a way to turn that intuition into numbers:

- visibility to the left, for example 18 metres,

- an assumed maximum speed for a pedestrian, for example 2 m/s,

- the vehicle’s own reaction time and braking capability.

Only with these inputs can the system calculate whether entering the intersection at a given speed is actually justified or not.

What does Demo 1.1 actually do?

The core idea of Demo 1.1 is simple: we measure how far an automated vehicle can reliably see in different directions in bad weather – and express it in metres.

In practice, this means three things:

- Sectors and metres

The vehicle “splits” its surroundings into sectors: e.g. left, straight ahead and right. For each sector, it estimates how far the road and potential obstacles are visible with sufficient confidence. The resulting output could look like: “I now see 32 m ahead, 21 m to the left and 25 m to the right.” - Combining multiple sensors

In our Lapland dataset we use a gated camera, 4D radar and lidar together. The gated camera reduces the disturbing effect of snowflakes and is aimed far ahead, the radar helps to see through spray and fog and measures object speeds, and the lidar provides an accurate three-dimensional point cloud at shorter ranges. The goal is not to find a single “perfect” sensor, but to obtain an honest visibility estimate from their combination.

A clear signal for decision-making

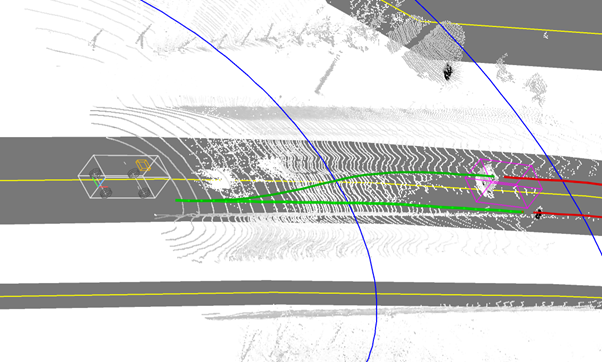

The algorithms for visibility estimation vary, but the vehicle’s control system ultimately needs a simple answer: is the visibility sufficient for this manoeuvre or not? That is why the visibility in metres is also translated into how far ahead the system can see along its own lane or the planned overtaking path (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Camera view to the front (top). Bottom: lidar point cloud on OpenStreetMap. The current trajectory and possible overtaking trajectories turn red at the preceding car, indicating a no-go.

Humans, self-driving cars, and trust measured in metres

It is often assumed that a self-driving car with a 360° sensor coverage automatically sees better than a human. In reality, things are more nuanced:

- humans can see rather far, detect motion and make use of incomplete information,

- automated vehicles, in turn, never get tired, measure distances and speeds precisely, and are often tuned to see especially well at short range to enable emergency stops at low speeds.

In winter automation, the goal is not yet to beat human drivers in every situation, but first to enable automated driving in winter at all:

- to assess when visibility is sufficient and when it is not,

- to slow down in time, or ask a human driver (or potentially a remote operator) for help.

In the bigger picture, the Cynergy4MIE project is one building block towards a world where winter automation is not a black box, but a system that recognises its limits and can turn trust into numbers. We want to be able to measure safety margins reliably – even in a Lapland snowstorm.

Blog signed by: VTT team